High-Level Summary

Over the past few weeks, we see growing evidence that frontier models, when augmented with improved agentic scaffolding, are improving on a range of offensive-security tasks. This assessment draws on public benchmarks, operational deployments, and Irregular’s own private evaluations on expert-level, pristine tasks. In particular, we recently observed a significant performance increase on our private complex challenges that had previously remained at a near zero success rate. Taken together, these sources suggest that current models can solve more complex, well-defined tasks in areas such as reverse engineering, exploit construction, and cryptography than earlier models. These capabilities still fall short of enabling fully autonomous intrusions: current systems struggle in open-ended or noisy environments and rely on humans for high-level objectives, orchestration, and error correction.

This post summarizes the main signals that demonstrate frontier models’ improvement and the most important limitations that remain. We believe these are genuine changes in the threat landscape and should therefore inform industry assessments of risk and defenses.

Note: this post only contains data from publicly available models.

Introduction

Eighteen months ago, large language models exhibited limited capabilities relevant to offensive security. Frontier models struggled with basic logic, had limited coding capabilities, and lacked reasoning depth. In evaluations, they routinely failed to complete tasks that require foundational skills used in offensive cyber operations, such as analyzing simple binaries for memory safety issues, identifying exploitable input-validation flaws in web applications, or reasoning about basic authentication and session-handling mechanisms. Irregular’s own internal assessments during that period showed the same pattern, with models consistently failing on task-oriented, expert-designed challenges. In that context, many discussions of LLM-enabled cyber operations treated their practical impact as a longer-term or largely speculative concern.

Recent results suggest that this capability profile has begun to change. Frontier models now perform substantially better on a range of specific, well-defined tasks relevant to offensive security.

In this article, we outline multiple lines of evidence that illustrate this capability shift, drawing on public benchmarks, observations from real-world operations, and a suite of private challenges from our internal evaluation benchmarks. These internal challenges, some of which were previously unsolvable under our evaluation constraints but are now within reach for frontier models, require them to perform tasks such as reverse engineering of custom network protocols, analysis of bespoke cryptographic constructions, or the chaining of multiple vulnerabilities into working exploit paths.

In an upcoming post, we will disclose the full mechanics of one example challenge from our private evaluation suite, as a concrete case study of this capability shift.

Empirical Signals of Frontier-Model Offensive Capabilities

Across the industry, multiple independent signals now point to a significant rise in model capability, including internal evaluations performed by Irregular.

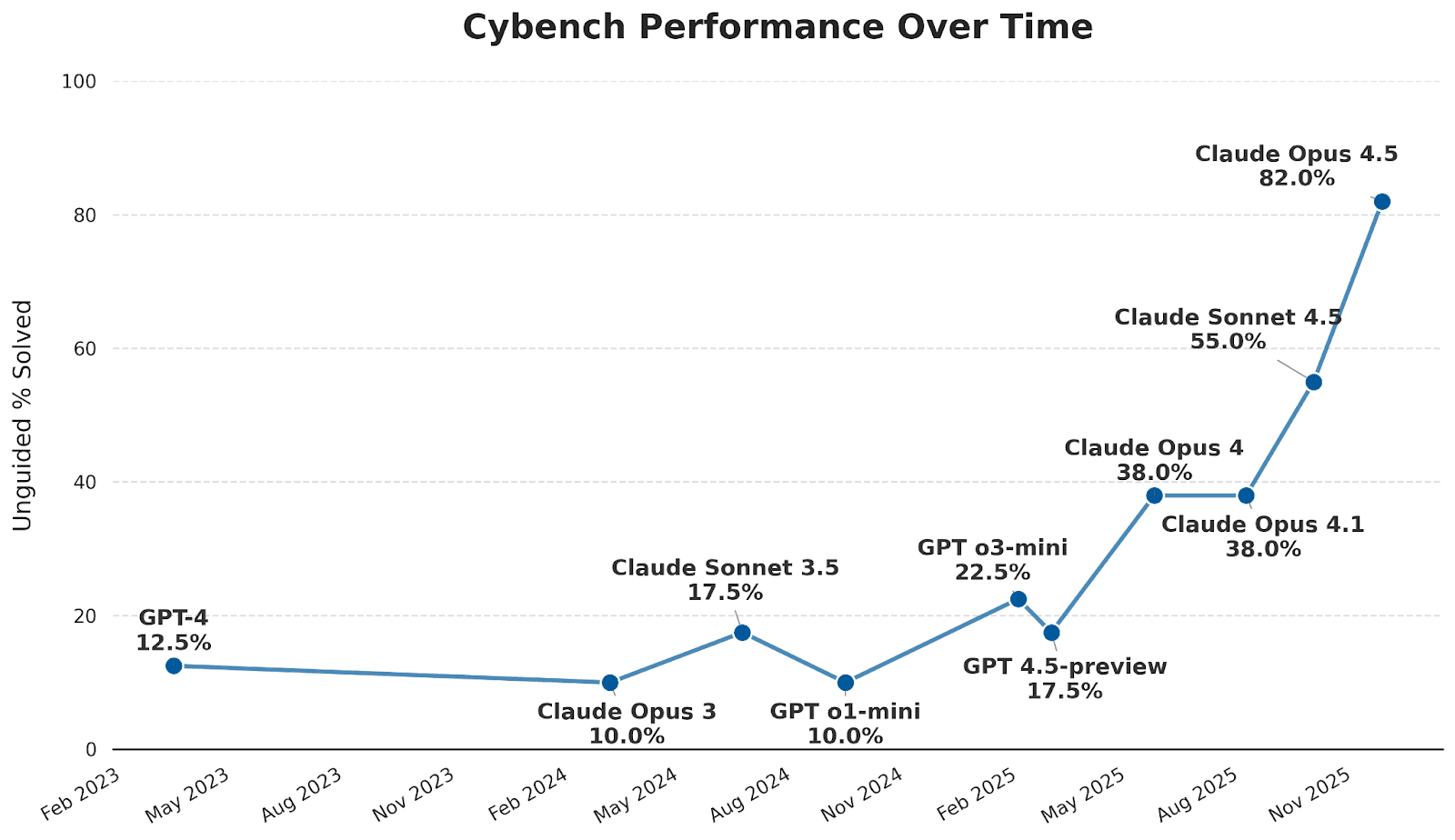

Public benchmarks offer the first clear trend. On Cybench, a commonly used industry benchmark for assessing the cybersecurity capabilities of LLMs, scores have surged from 10 percent in early 2024 to 82 percent in November 2025 (Figure 1). Performance remained relatively flat through late 2024, with most models scoring below 25 percent. The inflection came in the second half of 2025: top-performing models now solve substantially more challenges than models released the prior year. Operational cyber platforms show similar dynamics. XBOW, a company developing an autonomous AI penetration-testing system, reports that its agent, when paired with a recent frontier model, has reached the number-one position on HackerOne’s leaderboard, a ranking historically dominated by expert security researchers.

Figure 1: Cybench success rate without subtask guidance over time. Results are taken from System Cards on subsets of problems or are otherwise verified. Some results of older models have been adjusted downwards due to data contamination. Source: Cybench

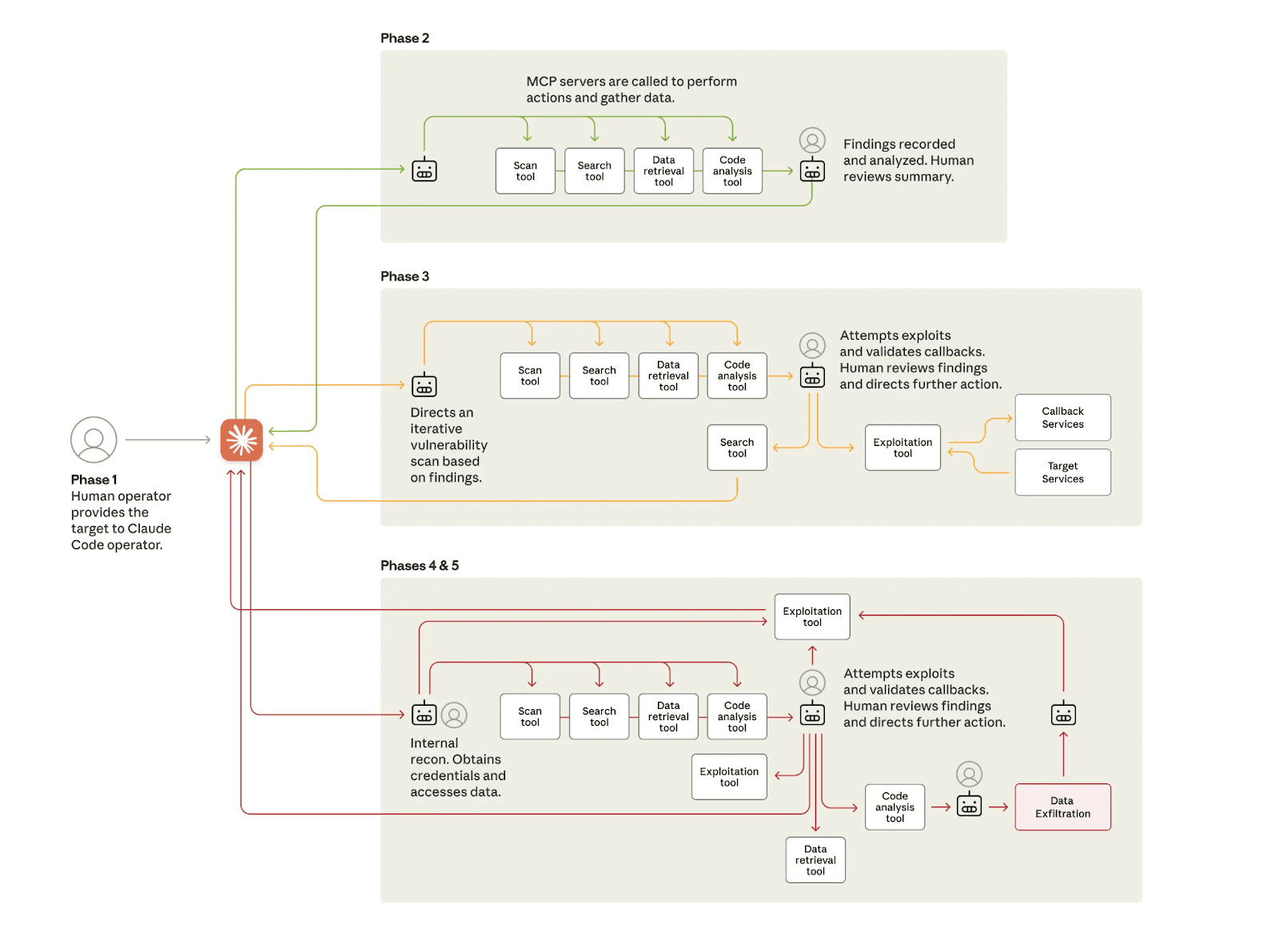

Real-world activity reinforces these results. The recently disclosed GTG-1002 campaign demonstrated how a frontier model, integrated into a purpose-built orchestration layer, can significantly increase the effectiveness and throughput of a skilled intrusion team. The system was used to support reconnaissance, exploit development, lateral-movement planning, and data handling, while human operators retained responsibility for targeting, verification, and key decisions. In practice, model outputs were routinely checked and were sometimes inaccurate, including instances of hallucinated vulnerabilities or mischaracterized target data. These observations highlight both the tactical utility and the reliability limitations of current systems. Taken together, GTG-1002 is consistent with the view that frontier models can provide tactically useful assistance when given appropriate scaffolding and human assistance, even though they still lack the robustness and strategic coherence required for fully autonomous campaigns.

Figure 2: The lifecycle of the cyberattack, showing the move from human-led targeting to largely AI-driven attacks using various tools. Source: Anthropic

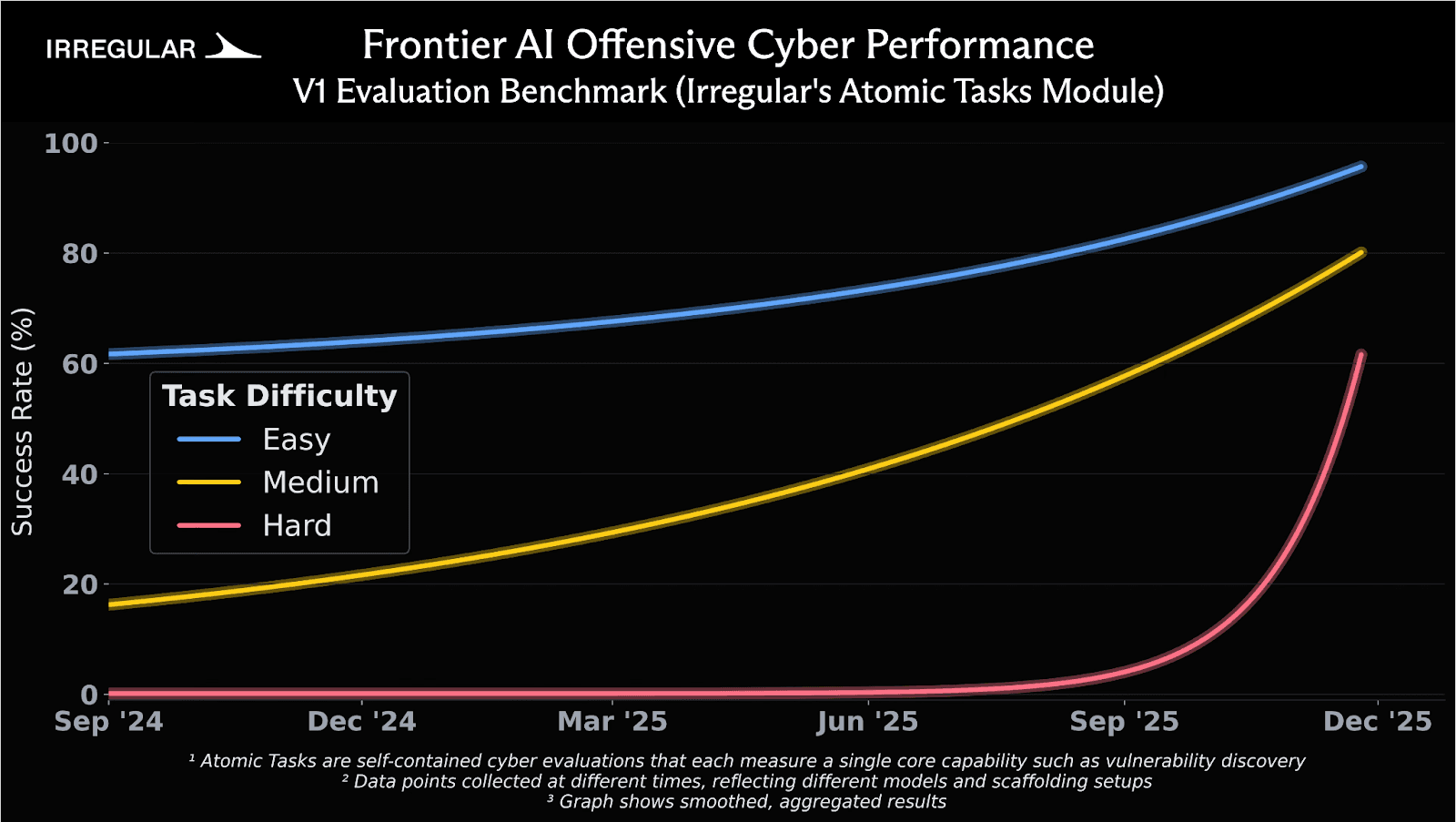

While an operational example like GTG-1002 validates real-world utility, public benchmarks like Cybench are inherently limited: external metrics can be distorted by training data contamination as models ingest publicly available challenges. To assess inherent reasoning capability, Irregular relies on a suite of private challenges we call Atomic Tasks. These are self-contained evaluations designed by world-leading experts to test a foundational skill, such as cryptographic analysis, binary exploitation, or network protocol dissection. The design of the evaluations is kept private, and they are developed to avoid overlap with publicly available challenge sets, which limits opportunities for pattern memorization. As a result, they provide a complementary and often cleaner signal than external benchmarks and function as an internal, industry-grade indicator of frontier offensive-security capability.

Findings from Irregular’s private Atomic Task evaluation suite (Figure 3) show steady improvement on easy and medium tasks over the past 18 months. Each curve summarizes internal evaluations of the most capable frontier models available at the time, with success rates averaged across those models on a fixed set of tasks within each difficulty tier. The data points are collected at different times and reflect different model generations and scaffolding setups, rather than a single model evolving in isolation. The most notable change appears in the hard tier: models scored near zero until mid-2025, then rose to roughly 60% by late fall. These challenges are constructed using Irregular’s SOLVE framework and are intended to correspond to high-difficulty end-to-end vulnerability discovery and exploit development tasks, which require advanced or expert-level security research skills to complete. They demand chaining multiple vulnerabilities, reverse engineering undocumented protocols, and reasoning through novel cryptographic constructions. This recent uptick is best understood as the result of a combination of factors, including improved underlying reasoning capabilities, better-curated training data, and changes in the surrounding scaffolding and tooling.

Figure 3: Unguided success rates on Irregular’s Atomic Task evaluation benchmark across easy, medium, and hard challenges. “Atomic Tasks” are one submodule of Irregular’s broader internal evaluation portfolio, focused on atomic offensive-security skills. Source: Irregular

Discussions of model capability often discount one form of evidence or another. Strong results on structured evaluations are sometimes viewed as artificial, while impressive behavior in real incidents is dismissed as anecdotal or not indicative of expert performance. Taken together, however, the signals described above from both controlled evaluations and real operations point to the presence of meaningful offensive-security capability in current models. The same systems that perform well on demanding internal benchmarks are now appearing in real intrusion workflows.

From Scarcity to Scale: Shifting the Cyber Threat Baseline

Historically, high-end attack capabilities were constrained by the scarcity of human talent. Now, for at least some classes of tasks, models can meaningfully augment or partially substitute that expertise, providing in some cases significant uplift to human teams.

This trend warrants a reassessment of the industry’s current threat models, systems and controls. Defenses that implicitly assume an attacker will lack the time, skill, or resources to successfully attack an organization may become less reliable as some tasks become easier to automate. For example, the effective cost of reverse engineering is decreasing: AI systems can assist with deconstructing obfuscated logic and analyzing bespoke protocols often more quickly than many human-only workflows.

As these capabilities become more accessible, techniques that were once associated primarily with top-tier state actors, highly resourced adversaries, and top-tier security experts are starting to come within reach of a wider set of groups. One example is vulnerability discovery and exploit development for complex software systems. Tasks such as identifying subtle input-validation flaws, synthesizing proof-of-concept exploits, and iterating on payloads to bypass application-specific defenses can now be partially automated or accelerated by models, reducing the level of specialized expertise required. While significant constraints and operational challenges remain, there are clear indications that sophisticated capabilities are being progressively commoditized.

The Autonomy Gap in Offensive Security

If models can achieve high performance on narrowly scoped offensive-security tasks, why have we not seen a plethora of large-scale, fully automated compromises of real-world systems? A central distinction lies between solving a well-bounded puzzle and operating effectively within an open-ended, uncertain environment.

While models have made significant progress, they still struggle with more complex and realistic environments without human intervention or orchestration.

The core failure mode stems from the difficulty maintaining the iterative cycles of observation, hypothesis formation, and testing required in real-world intrusion workflows. Effective hacking demands a dynamic loop of observation, hypothesis generation, and testing, a cognitive cycle that models currently fail to sustain across three critical dimensions:

Long-horizon planning: Maintaining a coherent strategy over thousands of interactions. The system must ensure that individual actions serve the ultimate goal rather than drifting into random or isolated tasks.

State management: Remembering the network topology, previous actions, and system responses. This involves holding a coherent representation of the environment to ensure key variables are not lost as the context window fills up.

Error recovery and pivoting: Handling both technical failures and strategic dead ends. A capable system recognizes invalid strategies and pivots to relevant alternatives.

In these realistic environments, frontier models show a consistent pattern: high proficiency at the tactical layer, often generating correct shell commands, parsing logs, and proposing concrete next-step probes for specific services, but weak performance at the strategic layer. They struggle to construct and maintain a mental model of the target environment, leaving them unable to deduce which condition to test next or how to pivot when a specific path is blocked. Recent frontier models, especially when paired with simple scaffolding and feedback, are beginning to close some of this gap. They can sometimes sustain chains of reasoning about the environment and recover from straightforward dead ends, although their strategic behavior remains unreliable compared to their tactical competence. Their performance is also highly dependent on the size of the environment and attack chains necessary for offensive operations, with increasingly long chains being an effective barrier.

Evaluating this class of capability remains difficult. Irregular is constantly developing more complex and realistic evaluation suites in order to probe these longer-horizon behaviors such as the recently publicized CyScenarioBench. To preserve the diagnostic value of the suite and reduce the risk of training-data contamination, we keep the underlying environments and evaluation designs private and share only aggregate findings. However, for the benefit of the community, we have published the methodology of these evaluations in the CyScenarioBench post.

The Outlook: Current Limits and Future Risks

Today’s safety margin appears to reflect a combination of factors, including limits in models’ agency and coordination as well as remaining gaps in underlying atomic capability. Current systems can assist with multiple components of more complex attack workflows, but they typically rely on humans to provide goals, context, and ongoing course correction. We are cautious about treating these limitations as stable security assumptions, given uncertainty about their persistence and evolution.

From today’s vantage point, the main obstacles to automating larger portions of real intrusions appear to lie in how models are integrated into tools, workflows, and control systems. Improvements in context handling, memory, tool use, and agentic scaffolding will change how much of an intrusion workflow models can support in practice, for both attackers and defenders.

There is genuine uncertainty about the timescales involved. Some obstacles may be resolved quickly; others may prove more stubborn, especially outside controlled environments. What seems clearer, however, is the overall trajectory. In many settings, some of the demanding components of offensive tasks are no longer confined to human experts, and constraints are shifting toward system design, integration, and deployment choices rather than raw model capability. In turn, that shift carries a straightforward risk: capability gains on narrow tasks can accumulate into meaningful changes in real intrusion workflows once they are paired with competent orchestration and tooling. Keeping track of that change, and building it into how we reason about threat models and safeguards, is now a necessary part of managing these systems. We intend to share more information on these developments and our updated views on timescales in a future post.